In computer graphics, coordinates in 3D space are generally represented not as 3 values, but 4. This is because we use 4D projective space to represent 3D Euclidean space. The idea is simple: a 4D vector in projective space $(x,y,z,w)$ represents the 3D point $(x/w,y/w,z/w)$ in Euclidean space. But explaining why we do it like this is a bit more involved, and this is what I hope to achieve here.

Intersection of Two Lines

To keep things simple, we will focus our discussions on 2D Euclidean space instead of 3D for the time being. When working in 2D Euclidean space, we often analogously use 3D projective space to represent 2D Euclidean space.

To motivate 3D projective space, we start with an unrelated problem. Consider two lines in 2D Euclidean space. Under what conditions will the lines intersect? The answer is obvious: two lines will always intersect, unless they are parallel to each other.

Two lines always intersect unless they are parallel to each other. Image source.

From a purely abstract standpoint however, this condition is cumbersome to work with. Anytime we want to discuss about lines and their intersections, we have to consider different cases depending on whether or not the lines are parallel. Moreover, given two random lines, they are not parallel almost surely (from a measure theoretic standpoint), and hence have an intersection almost surely. So it would be nice if we can define things so that even parallel lines have an intersection in some sense.

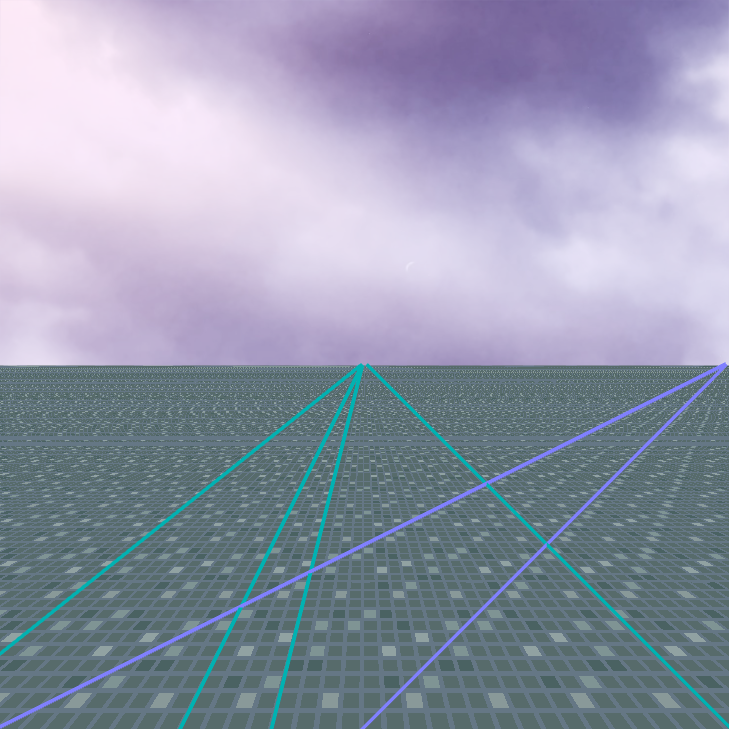

And indeed, there is a sense in which that happens! If you add an additional dimension and view your two parallel lines from 3D Euclidean space, they appear to intersect at a point infinitely far away on the horizon.

Parallel lines intersect at the horizon, when viewed in 3D.

This intersection point at the horizon is aptly named the “point at infinity”. And you will have noticed in the diagram above that there are indeed multiple points at infinity, each of which correspond to the direction that the parallel lines point in. Hence it makes sense to use a 2D vector $(x,y)$, interpreted as a direction vector, to characterise different points at infinities e.g. a vector of $(1,2)$ represents the point at infinity at which parallel lines with direction $(1,2)$ intersect. Note that the choice of direction vector $(x,y)$ is not unique; different vectors $(2,4)$ or $(-1,-2)$ would represent the same point at infinity. This will be important in a moment.

Defining 3D Projective Space

At this point we need to introduce some kind of system that differentiates between “regular” points in 2D Euclidean space, and these so-called “points at infinities” so that we know which one we’re talking about. This will end up turning out to be exactly 3D projective space.

The simplest way to differentiate betwen these two kinds of points is to introduce an additional boolean variable $w\in\{0,1\}$ indicating whether a vector $(x,y)$ represents the point at infinity corresponding to the direction $(x,y)$ or the “regular” 2D Euclidean point $(x,y)$ i.e. we consider the space

\[\mathcal P^3:=\mathbb R^2\times\{0,1\}.\]Mathematically, though, this is not very elegant nor satisfying, and there is no clear connection between points at infinity and points in 2D Euclidean space. Instead, we can try introduce a real-valued variable $w\in\mathbb R$, and depending on the value of $w$, interpret the point one way or another i.e. we consider the space

\[\mathcal P^3:=\mathbb R^2\times\mathbb R.\]To motivate which values of $w$ should correspond with what, recall from our discussion earlier that for points at infinity, the choice of direction vector $(x,y)$ is not unique; in fact any direction of the form $(\lambda x,\lambda y)$ for any $\lambda\neq 0$ corresponds to the same point at infinity. This motivates us to define two vectors $(x_1,y_1,w_1),(x_2,y_2,w_2)\in\mathcal P^3$ to be equivalent if $(x_1,y_1,w_1)=(\lambda x_2,\lambda y_2,\lambda w_2)$ for some $\lambda\neq 0$ (for mathematically inclined readers, you can easily check that this is indeed an equivalence relation). We want to define things so that two vectors in $\mathcal P^3$ are equivalent if and only if they correspond to the same point, whether they represent a point at infinity or a point in 2D Euclidean space.

Hence, if $(x,y,w)$ corresponds to a point at infinity then we want $(\lambda x,\lambda y,\lambda w)$ to correspond to the same point at infinity, for all $\lambda\neq 0$. Likewise if $(x,y,w)$ corresponds to a point in 2D Euclidean space, we want $(\lambda x,\lambda y,\lambda w)$ to correspond to the same point in 2D Euclidean space as well. Because this needs to hold for all $\lambda\neq 0$ the only choice is that $w=0$ represents points at infinity and $w\neq 0$ represents points in 2D Euclidean space, or vice versa. It doesn’t really matter which one you pick, but the convention is to take the former approach.

When $w=0$, indicating a point at infinity, we can take the direction vector of the point at infinity by simply looking at the first two variables $(x,y)$. By construction, all equivalent vectors are of the form $(\lambda x,\lambda y,0\lambda)$ which describe points at infinity with direction vector $(\lambda x,\lambda y)$ and this is exactly what the original vector $(x,y,0)$ describes. E.g. the vector $(1,2,0)$ represents the point at infinity with direction vector $(1,2)$, and this is equivalent to the vector $(2,4,0)$ or indeed any vector of the form $(1\lambda,2 \lambda,0)$ for $\lambda\neq 0$.

When $w\neq 0$, indicating a point in 2D Euclidean space, we have to do a bit more work because we need to explicitly satisfy the condition we imposed that vectors in $\mathcal P^3$ should be equivalent if and only if they correspond to the same point in 2D Euclidean space. After a bit of thinking, the most natural way to do this is to map $(x,y,w)$ to the 2D Euclidean point $(x/w,y/w)$. This works because now all the vectors in an equivalence class $E_\lambda:={(\lambda x,\lambda y,\lambda w)}$ are mapped to a single point $(\lambda x/\lambda w,\lambda y/\lambda w)=(x/w,y/w)$ in 2D Euclidean space.

Furthermore, note that as $w\to 0$, the corresponding points in Euclidean space $(x/w,y/w)$ approach the point at infinity with direction vector $(x,y)$ (since $(x/w,y/w)$ is a rescaling of $(x,y)$ by $1/w$ which approaches infinity as $w\to 0$). This confirms that the definitions we made make sense.

Summary

3D Projective Space

A vector $\vec v=(x,y,w)$ in 3D projective space has the following interpretation

-

If $w=0$ then $\vec v$ represents the point at infinity with direction vector $(x,y)$.

Note that we need to exclude the case $x=y=w=0$ since $(0,0)$ is not a valid direction vector.

-

If $w\neq 0$ then $\vec v$ represents the point $(x/w,y/w)$ in 2D Euclidean space.

Formally, 3D projective space is defined as follows.

3D Projective Space

Definition: 3D projective space is the set of equivalence classes \(\mathbb P^3:=\left(\mathbb R^3\setminus\{0,0,0\}\right)/\sim\)

where $\sim$ is the equivalence relation given by

\[(x_1,y_1,w_1)\sim(x_2,y_2,w_2)\iff (x_1,y_1,w_1)=(\lambda x_2,\lambda y_2,\lambda w_2)\text{ for some }\lambda\neq 0.\]Higher Dimensional Projective Spaces

We can apply the same argument as above but for 3D Euclidean space and 4D projective space, by increasing all the dimensions by one, and replacing the problem of intersecting lines with intersecting planes. This leads us to define the following.

4D Projective Space

A vector in 4D projective space, described by $\vec v=(x, y, z, w)$ has the following interpretation

- If $w=0$ then $\vec v$ represents the point at infinity with direction vector $(x,y,z)$, with the point $x=y=z=w=0$ excluded

- If $w\neq 0$ then $\vec v$ represents the point $(x/w,y/w,z/w)$ in 2D Euclidean space.

Formally, 4D projective space is defined as follows.

4D Projective Space

Definition: 4D projective space is the set of equivalence classes \(\mathbb P^4:=\left(\mathbb R^4\setminus\{0,0,0,0\}\right)/\sim\)

where $\sim$ is the equivalence relation given by

\[(x_1,y_1,z_1,w_1)\sim(x_2,y_2,z_2,w_2)\iff (x_1,y_1,z_1,w_1)=(\lambda x_2,\lambda y_2,\lambda z_2,\lambda w_2)\text{ for some }\lambda\neq 0.\]In general, $n$ dimensional projective space is defined as you would expect.

n Dimensional Projective Space

Definition: $n$ dimensional projective space is the set of equivalence classes \(\mathbb P^n:=\left(\mathbb R^n\setminus \vec{0}\right)/\sim\)

where $\sim$ is the equivalence relation given by

\[v_1\sim v_2\iff v_1=\lambda \cdot v_2\text{ for some }\lambda\neq 0.\]However, in computer graphics, we usually usually stick to 4D projective space.

Linear Transformations in Projective Space

So far we’ve seen the motivation behind defining projective space as a way of addressing the inconvenience that two parallel lines (or in general, two hyperplanes) never intersect in Euclidean space. However, this is not the reason why projective space is used in computer graphics.

Projective space is used in computer graphics because it allows us to describe not only linear transformations, but also certain nonlinear transformations in Euclidean space (in particular, translations and projections) as linear transformations in projective space. This means that these transformations can be represented as matrix operations, which a modern GPU can perform very quickly.

Specifically, a vector $(x,y,z)\in\mathbb R^3$ can be represented by a vector of the form $\vec v=(\lambda x,\lambda y,\lambda z,\lambda)\in\mathbb P^4$ where $\lambda\neq 0$. Suppose we multiply $\vec v$ by a matrix $A\in\mathbb R^{4\times 4}$ resulting in \(\vec v':=A\vec v\in\mathbb P^4\) which we then interpret as a point in 3D Euclidean space (or possibly as a point at infinity). We will show that such a transformation captures not only linear transformations but also certain nonlinear transformations like the ones described above.

First, however, we need to verify that this operation is well-defined. We need to do this because the representation of $(x,y,z)\in\mathbb R^3$ in projective space $\mathbb P^4$ is not unique. Specifically, if $(x,y,z)$ is described by two different vectors in $\mathbb P^4$ we need to show that after applying the above procedure, the resulting two vectors in $\mathbb R^3$ (or possibly points at infinity) are the same.

The proof below will show that this is also valid for points at infinity which also have an ambiguous representation in projective space of the form $(\lambda x,\lambda y,\lambda z,0),\lambda\neq 0$.

Proof

Let $\vec v_1:=(\lambda_1x,\lambda_1y,\lambda_1z,\lambda_1),\vec v_2:=(\lambda_2x,\lambda_2y,\lambda_2z,\lambda_2)\in\mathbb P^4$ be two vectors in the same equivalence class (representing the same point in 3D Euclidean space) with $\lambda_1,\lambda_2\neq 0$. Define $\vec u:=(x,y,z,1)$. Then,

\[\begin{align*} A\vec v_1&=A\cdot \lambda_1\mathbb I\cdot \vec u\\ &=\lambda_1(A\vec u). \end{align*}\]Similarly,

\[\begin{align*} A\vec v_2&=A\cdot \lambda_2\mathbb I\cdot \vec u\\ &=\lambda_2(A\vec u). \end{align*}\]Since $\lambda_1,\lambda_2\neq 0$ it follows that $\lambda_1(A\vec u)\sim\lambda_2(A\vec u)$ hence they correspond to the same point in 3D Euclidean space, or the same point at infinity.

If we are in the case where $\vec v_1:=(\lambda_1x,\lambda_1y,\lambda_1z,0),\vec v_2:=(\lambda_2x,\lambda_2y,\lambda_2z,0)\in\mathbb P^4,\lambda_1,\lambda_2\neq 0$ representing the same point at infinity, then the exact same argument holds.

Proof notes

Note that the crux of the proof relied on how we define the equivalence relation $\sim$. If we had defined it differently, the proof may not even follow through, so this is another good justification for the choices we made along the way!

Translations

With that out of the way, we now discuss how to represent translation in Euclidean space which is a nonlinear transformation, as a linear transformation in projective space. A translation of $(t_x,t_y,t_z)$ can be represented by the matrix

\[A=\begin{bmatrix} 1&0&0&t_x\\ 0&1&0&t_y\\ 0&0&1&t_z\\ 0&0&0&1 \end{bmatrix}.\]Applying this to a vector $(x,y,z)$ in Euclidean space, we would hope that the vector would be mapped to $(x+t_x,y+t_y,z+t_z)$. Applying this to a point at infinity however, it should make intuitive sense that nothing should happen, since a translation by a finite distance should not move any points that are at infinity.

It is not too hard to show that this is exactly what happens!

Solution

Let $(x,y,z)$ be a point in Euclidean space, and $\vec v:=(x,y,z,1)$ be a corresponding point in projective space (note that due to the result above it doesn’t matter what point in the equivalence class we choose, so we pick the simplest choice which is $\lambda=1$). Then

\[\begin{align*} A\vec v&=\begin{bmatrix} 1&0&0&t_x\\ 0&1&0&t_y\\ 0&0&1&t_z\\ 0&0&0&1 \end{bmatrix}\cdot\begin{bmatrix} x\\y\\z\\1 \end{bmatrix}\\ &=\begin{bmatrix} x+t_x\\y+t_y\\z+t_z\\1 \end{bmatrix} \end{align*}\]which represents the point $(x+t_x,y+t_y,z+t_z)$ in Euclidean space as expected.

If $(x,y,z)$ represents a point at infinity, then let $\vec v:=(x,y,z,0)$ and we have

\[\begin{align*} A\vec v&=\begin{bmatrix} 1&0&0&t_x\\ 0&1&0&t_y\\ 0&0&1&t_z\\ 0&0&0&1 \end{bmatrix}\cdot\begin{bmatrix} x\\y\\z\\0 \end{bmatrix}\\ &=\begin{bmatrix} x\\y\\z\\0 \end{bmatrix}. \end{align*}\]which is the original point at infinity unchanged.

Projections

Another nonlinear but highly useful transformation in computer graphics is the process of projecting a 3D scene onto a 2D screen. In a subsequent page we will discuss this topic in depth including how to derive the following equation, but for now, know that we end up needing to compute the transformation

\[\begin{bmatrix}x\\y\\z\end{bmatrix}\mapsto\begin{bmatrix} -\frac nr\cdot\frac xz\\ -\frac nt\cdot\frac yz\\ \frac{f+n}{f-n}+\frac{2fn}{f-n}\cdot\frac 1z \end{bmatrix}\]where $n,f,r,t$ are constants.

This can be written as a linear transformation in projective space but is a bit trickier to figure out. As above, we need to find a matrix $A\in\mathbb R^{4\times 4}$ such that

\[\begin{bmatrix} x'\\y'\\z'\\w'\end{bmatrix}=A\cdot\begin{bmatrix} x\\y\\z\\1\end{bmatrix}\]where $(x’,y’,z’,w’)$ represents the output.

Solution

The first thing to notice is that in the Euclidean version of the output, all the components are divided by $z$, which suggests setting the last row of $A$ to be $(0,0,1,0)$ so that $w’=z$. We can easily fill out the first rows of $A$ as $(-n/r,0,0,0)$ and $(0,-n/t,0,0)$ respectively to match the desired output. This gives us

\[A=\begin{bmatrix} -\frac nr&0&0&0\\ 0&-\frac nt&0&0\\ ?&?&?&?\\ 0&0&1&0 \end{bmatrix}.\]Looking at the third row, it is unlikely that we need to use the values of $x$ and $y$ to calculate $z’$ hence we can set the first two entries to 0. Let the last two entries be $\alpha,\beta$ respectively. Then equating $z’$ to the corresponding matrix calculations, we get

\[\frac 1z(\alpha z+\beta)=\frac{f+n}{f-n}+\frac{2fn}{f-n}\cdot\frac 1z\]hence $\alpha=\frac{f+n}{f-n},\beta=\frac{2fn}{f-n}$.

In full, the matrix $A$ is

\[A=\begin{bmatrix} -\frac nr&0&0&0\\ 0&-\frac nt&0&0\\ 0&0&\frac{f+n}{f-n}&\frac{2fn}{f-n}\\ 0&0&1&0 \end{bmatrix}.\]Linear Transformations

We stated without proof above that linear transformations in projective space capture not only linear transformations in Euclidean space, but also some nonlinear transformations such as translations and projections as we just saw. We still need to show that transformations in projective space include linear transformations. Can you see how?

Solution

Let $T\in\mathbb R^{3\times 3}$ denote the matrix form of a linear transformation in 3D Euclidean space. Define the block matrix

\[A=\begin{bmatrix} T&0\\ 0&1 \end{bmatrix}\in\mathbb R^{4\times 4}.\]If $(x,y,z)$ is a point in 3D Euclidean space, then letting $\vec v:=(x,y,z,1)$ as usual, we have

\[\begin{align*} A\vec v&=\begin{bmatrix} T&0\\ 0&1 \end{bmatrix}\cdot\begin{bmatrix} x\\y\\z\\1 \end{bmatrix}\\ &=\begin{bmatrix} T\cdot\begin{bmatrix} x\\y\\z \end{bmatrix}\\ 1 \end{bmatrix}. \end{align*}\]which is $T$ applied to the point $(x,y,z)$ in Euclidean space.

If $(x,y,z)$ represents a point at infinity, then letting $\vec v:=(x,y,z,0)$ we have

\[\begin{align*} A\vec v&=\begin{bmatrix} T&0\\ 0&1 \end{bmatrix}\cdot\begin{bmatrix} x\\y\\z\\0 \end{bmatrix}\\ &=\begin{bmatrix} T\cdot\begin{bmatrix} x\\y\\z \end{bmatrix}\\ 0 \end{bmatrix}. \end{align*}\]which is $T$ applied to the direction vector of the point at infinity.

Identity transformation

Finally, a quick note that transformations of the form \(A=\lambda\mathbb I\in\mathbb R^{4\times 4}\) for $\lambda\neq 0$ applies the identity operation i.e. leaves the inputs unchanged. This follows directly from how we defined the equivalence relation $\sim$.